For reference, I’m taking the following as given: climate change is real, it is caused by fossil fuel emissions, and the goal of a post-carbon energy future is an admirable one. At this point in the 21st century, I believe most well-informed people would agree with the above, but there are nuances to each of these issues which prevents global consensus.

Climate change may be real, but its impact both short and long-term is unknown. The same could be said for the effect carbon emissions have on climate. We know it’s increasing average temperatures, but the exact cause and effect is poorly understood. Lastly, a post-carbon energy future is the ultimate goal in eventually restoring some kind of balance with the planet, but at what point can we make the switch? The answer to this question can be nebulous, black and white, or yet to be proven… depending on what you believe to be possible. The difficulty in answering this question is that energy touches almost every aspect of human civilization, so proposing any kind of dramatic shift in the way energy is produced, consumed, or priced will have profound effects on our society.

We Can’t Make the Switch Now

Energy is involved in heating, transportation, electricity and pretty much everything that makes our life awesome. Wouldn’t it be amazing if processes that didn’t leave a lasting impact on the planet powered all the awesome stuff? Of course it would, but if that is the ideal situation, why hasn’t a post-carbon transition happened yet? Simply, we do not have the technical capability yet to make this a reality and maintain our current standard of living. Currently, only 1% of all energy is currently generated by renewables (solar, wind, tidal, geothermal). Renewables are only really useful for generating electricity right now (electricity being roughly half of all energy use), but energy includes transportation and heating, which renewables are not suited for. Not even close actually.

Even electricity generated by renewables has drawbacks that other sources of electricity do not suffer from, namely, intermittency. Intermittency wouldn’t be a problem if there were techniques available to capture the energy renewables produced in anticipation of downtime, but these techniques do not exist. Inventing efficient, mass-storage for electricity is the most essential element for taking renewables seriously as a potential replacement for fossil fuels with respect to electricity production. Solar cells could become a million times as efficient as they are now, but if we can’t efficiently store the electricity generated, these solar cells will still be useless if it gets cloudy for a couple of days.

Currently, according to the International Energy Agency, fossil fuels make up around 81.6% of global energy (electricity, heating, and transportation). The reason this percentage is so high is two-fold: fossil fuels are relatively cheap (both in price and required infrastructure), and they’re such efficient energy sources. It’s true the cost of fossil fuels does not include externalities such as carbon emissions; so imposing carbon taxes to make them more cost competitive with renewables would certainly lead to a decrease in use. However, a price on carbon does not make natural gas less efficient at heating houses.

The main argument for not being able make the post-carbon switch is not that it would be really expensive (it would be), or that it would be too disruptive to the economy (it certainly would be), but that it just physically cannot be done. Even Truthout, hardly a publication protecting corporate interests, recognizes the severe limitations of renewables in Germany, Denmark, and Norway. These countries are usually examples of industrial societies that have already made the transition to a post-carbon energy future, but the examples fall apart upon closer inspection of their ‘clean’ credentials.

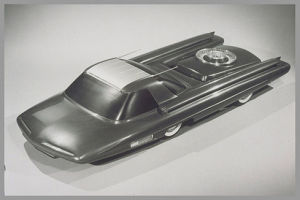

As much as we collectively might want to move past using fossil fuels, they are too energy dense not to use them. It’s not feasible to power a car or an airplane with solar panels. similarly, heating a Torontonian’s house in the winter with wind power is not really in the cards. Not yet anyway.

Is Zero Impact the Current Goal, or a Future Goal?

So, if it’s true that we can’t do away with fossil fuels yet without surrendering our material comforts, we have a couple of options: continue with our world-destroying lifestyle, or reduce our standard of living. Let’s take a look at the latter option very briefly, noting that the choice between ‘destroy our planet’ or ‘live like a cavemen’ is ludicrously simplistic. Say mankind forgoes material comforts to reduce the impact of global warming; the fulcrum of this balance would be where human activity had few residual impacts but still provided a modicum of civilization. Essentially, our balance would be giving up only what we need to do no-harm… Is this even possible?

Essentially, all human activity currently has an impact on the environment. Building a wind turbine is a massive construction project and involves using steel (and thus coal). The manufacturing of solar panels involves lead and cadmium, both of which are extremely toxic. Energy efficiency can go a long way, but always involves modern manufacturing processes with an environmental impact. Even if we were to revert to a human lifestyle akin to our 50,000 year old ancestors, if 7 billion people all started lighting camp fires at night, our forests would suffer greatly and campfires are actually less efficient and release more emissions than oil-based furnaces. The point being, everything we do has an environmental impact. So what we’re really looking for is a bridge that gets us to a place where we can eventually have zero impacts, or at least as little impact as possible.

We Need our Technological Society for the Post-Carbon Transition

To get to a point where our civilization can make the transition, we’ll need our current technological process to continue on its current trend towards exponential scientific discovery. My argument here is going to get slightly futurist-like, but any discussion on climate change ultimately devolves into guesses of what the future looks like. A writer’s opinion of today colours their view of what tomorrow might look like, and I’m no different. Your humble correspondent is optimistic that technological progress will eventually lead to a world where our energy sources no longer emit, that 3D printing will reduce the footprint of manufacturing, and that construction efficiency will virtually eliminate the need to heat our houses even in northern climates. However, the above technological advances will be impossible if we pull back voluntarily from the industrial civilization we’ve been enjoying for the past two hundred years.

This is not to say that changes aren’t required now. The world could certainly benefit from a reduction in conspicuous consumption, or from a move away from over-packaging the products we buy. If we alter these practices, it won’t have a noticeable impact on the trajectory of human understanding and will be valuable practice for thinking critically, in a collective fashion, about how we enjoy the benefits of a technologically advanced society. That being said, we can’t throw the baby out with the bath water. To get to a point where we can enjoy global communication, rely on computers to do the heavy mental lifting, and for our lives to be free of chores so we can pursue intellectual aims without destroying the planet, we are going to need fossil fuels for the time being.

We don’t have to like fossil fuels, but we have to recognize their importance to the civilization they’ve helped build and how central they still are to bridging our transition to a post-carbon future.

Another wonderful and readable essay from Sustainable Balance. Keep ’em coming!