Featured photo courtesy of Gregor Winter.

Introduction:

The day before I started a new job, it was a rainy winter’s day in North Vancouver, but I felt pretty good. I wanted to avoid trying to fit a gym session into my first couple days at the new job, so the day before I started I decided to go hard and make it count so I could take a few days off.

This workout was going to be a “pull” day, meaning I would work on deadlifts, weighted chinups, and pendlay rows. I had worked my way up to working sets of 395 lbs on deadlifts (meaning I was aiming for 5 reps at this weight). 400 lbs was so close I could taste it. That had long been my “I know I’ve made it when” goal.

Previously I had been working a job involving some awkward lifting but I figured I was so fit and strong that I could handle the job and intense strength training concurrently. However, while working, I did something to my lower back that made it sore for a few days, but then it went away. So, on this particular day, which was several weeks later, I warmed up and could tell that my back wasn’t 100%. But hey, I love progress and my ego was tied into this, so I kept going. I hit 4 reps at 395 lbs (a personal best), but definitely did not use picture-perfect form on the last rep. My back felt all right though, so I lowered the weight to 365 lbs for another work set.

I completed the first lift and was lowering the bar back down when I felt an extremely painful *ri-i-i-p* in my lower back, near where the original twinge had been. My hands let go of the bar and I stood up. As I bent down over to take the weight off the bar, searing pain at the site of the rip got me to stand up straight again. The guy next to me had to be enlisted to get the weight off the bar and put everything away. As I walked out of the gym, I knew that I had experienced my first real weight-lifting injury. Until that point I had had zero problems in 10 years other than some sore muscles after training, which is to be expected.

For the next two weeks I could not bend my back. It had to be perfectly straight up or I got shooting pains at the site of the injury. Getting in and out of a chair required serious focus. I did a little self-diagnosis (I can’t recommend this approach, but it’s what I always do), and figured I had torn a ligament near my hip. Having done something similar to my ankle years before I knew there was only one prescription: rest and time. Lots of time. My ankle took 4 months, so I could only assume this would be about 4 months as well. Boo-urns.

A Break from Weight-Lifting – What I Noticed:

After about a month of rest (other than walking around), my back was still sore but I was a lot more functional. I was able to engage in some physical activities again, but lifting weights was still out of the question. I started with some light activity: softball, biking, and pushups/chinups. My performance was actually pretty good fitness wise (although I did drop pop-flys at softball), which indicated that I was holding onto a lot of the strength I had gained prior to the injury. I was able to run really fast, jump really high, and throw really far. Actually, I felt like I was running faster and jumping higher than I’d been able to while in the gym lifting heavy 2-3 times a week.

My appetite also decreased, which I expected to happen. When I was lifting hard 2-3 times a week, I often felt ‘hollow’ in that I would sit down and eat for an hour straight (involving more than a pound of meat), and still would want more. The days after I hit advanced weights on big lifts (squats, deadlifts, etc), my appetite would be somewhat ridiculous to the point where it was becoming very time consuming. After the month off, I was still quite muscular and strong (other than the injured back), and I was satisfied with less food, which was freeing up time.

So there I was, ironically finding lifestyle benefits from staying out of the gym. I noticed 2 main advantages: one, my non-weight lifting athletic performance increased; and two, my appetite became much more reasonable (though still really big compared to most people, but that’s just me). Over the summer my back kept improving until I was able to start thinking about weightlifting again. My first visits to the gym were just to get re-oriented, but then I started challenging myself again. The upper body lifts were no problem, but squats left my back pretty sore and deadlifts were still way too painful to consider.

About 4 months post-injury I was still avoiding deadlifts but began pushing hard with the other lifts, including squats. I got up to about 330 lbs on the squat again, a day before a softball game. As I was biking to softball I could tell that my legs were very much still in recovery from the previous day’s squat session. The hills were harder, and I was dreading them to a certain degree. Once I got to the game, I noticed I couldn’t run as fast, or throw as far. My body just didn’t have the jump it had while I was not training intensely. The appetite was also back. Big lifts make for big meals.

I quickly realized that I needed at least 2 days or more of recovery between extreme weight sessions if my body was to perform near its peak again. Scheduling my weight sessions around sports was annoying since sports’ schedules change from week to week. It came to a crossroads: I had to choose whether to continue getting stronger and accept the fact that my athletic ability would be compromised most days, or I had to accept that I wasn’t going to get any stronger allowing my athletic performance to improve. Essentially:

Choice 1 – Gain more strength, but be sore and weak when doing anything else

Or

Choice 2 – Maintain (advanced) strength, and perform better at everything else

When I was a strength novice, I didn’t have to make this choice. Back when I thought 200-pound squats and 150 pound bench presses were immense, the recovery time wasn’t as long. I could play sports the next day, no problem, as long as I had been training regularly so the soreness wasn’t too bad. It was only when I took a break due to injury from advanced training that I noticed I could play harder by avoiding 300-pound squats and 400-pound deadlifts, at least for the few days before a game.

Six months post-injury I was able to deadlift intensely again, working my way back up to 380 pounds. I was able to do it, and felt fine in the gym, but I woke up the next morning with a very sore right hip. Like, bad sore. It’s been a month since I woke-up with that sore hip, and it is only now recovered to the point where I’m thinking about weight-lifting again.

This time I’m going to listen to my body, and make the decision that I’m strong enough.

The Diminishing Returns of Strength Training:

I have written a lot about the benefits of strength training, so I won’t get into it again here. If you’re curious, start here. When I started strength training, it was easy to make gains and I noticed nothing but benefits for a long time. Everything I did, I did better. I felt (relatively) superhuman when I played sports. I was running faster, jumping higher, throwing further, had more endurance, could take bigger impacts, and overall just felt more confident.

Once I became advanced, however, incremental increases in strength did not provide the same returns they did when I was a beginner. They were also a lot harder to attain. Going from a 150-pound squat to a 200-pound squat gave me a ton of new athletic ability. Going from a 300-pound squat to a 350-pound squat did not provide the same return on investment. It took a lot longer to get to a 350-pound lift from 300, the recovery time in between sessions was much longer, and I had to eat a lot. These circumstances applied to all my lifts.

On top of the increased recovery time, the risk of injuries from weight-lifting increases dramatically once you are advanced. Even without picture-perfect form I never got injured lifting weights when I was only moderately strong. There just wasn’t enough weight to do any serious harm. Once I got strong enough to handle serious loads, that’s when aches and pains became common. And if I didn’t have laser focus in the gym, it was straight-up dangerous.

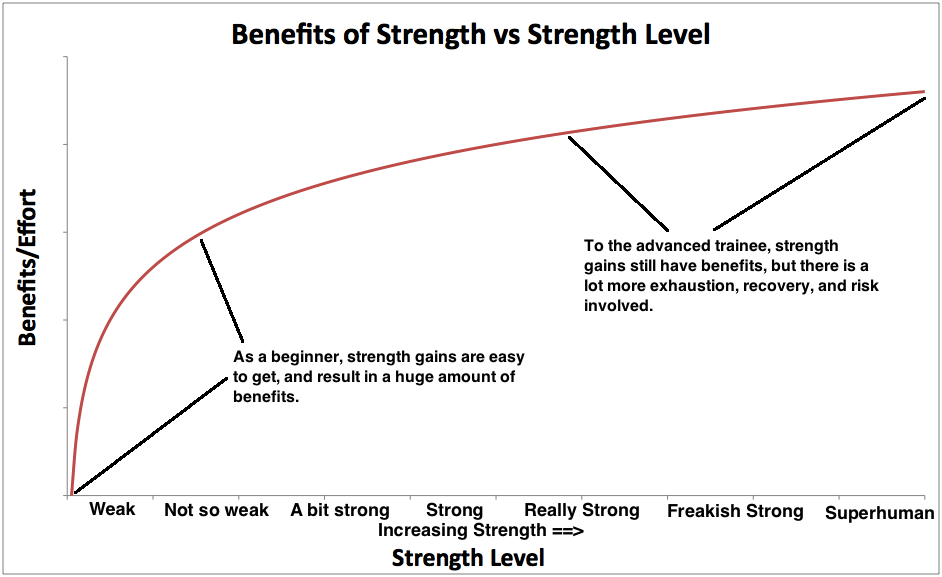

Part of me wants to be as strong as possible, but I realize now that it comes at too great a price (for me). If I wanted to be a master weight lifter (which I’m not even 100% sure I could be), it would be at the expense of too many other physical goals. I like biking places, playing spontaneous games of pickup, and I wouldn’t want to limit myself from taking up other physical hobbies. To stay at my current level of strength, 1-3 moderate to high intensity workouts a week are all that’s needed, which doesn’t require much recovery if the goal is only maintenance. To sum up these thoughts, I made the graph below. “Benefits/Effort” (benefits of additional strength divided by effort) on the vertical axis suggests that although strength gains always result in benefits, the effort to get that strength gets so large once you are advanced that it’s less attractive as a goal. Click on the graph below to get a better view of it.

The diminishing returns of strength training are real. The concept of being strong enough is an important one. Until this point, I had experienced nothing but benefits to being stronger, but eventually this was no longer the case.

What is Strong Enough?

This is not a reason to avoid weight lifting entirely as there are too many benefits to ignore, but it important to determine exactly what you want out of weight-lifting. If it’s just improved health, strength, athletic ability, and physique I would recommend the following goals (which are based on nothing but experience and observation):

Squat: 1.5 x bodyweight (175 pounder aims for 265 lbs) Deadlift: 1.8 x bodyweight (175 pounder aims for 315 lbs) Bench press: 1 x bodyweight (175 pounder aims for 175 lbs) Pullups: 8 consecutive solid pullups *If you’re female, shave a bit off these, unless you really want to go for it!

That’s it. If you can do all that, you are strong enough to obtain the vast majority of the benefits from strength training. To a beginner these may seem really advanced but it isn’t all that hard to achieve in 1-2 years with disciplined training, depending on the starting point. There will be individual variability due to different body types, so some of these goals will be easier to achieve than others, but there’s no reason almost anyone can’t do what’s described above if this is a goal for them.

The lack of return on investment that I’ve been mentioning only started to happen when I went well beyond these goals. Once I started thinking along these lines I looked into what professional athletes do for training. It turns out, as obviously as can be, that off-season training is inherently different from the training that occurs during a pro-sports season.

For a pro-athlete the goal of the off-season is to increase strength and conditioning to become a better athlete. During the actual sports season the goal is to win games. During the season an athlete who tries to set a personal record on the deadlift or squat the day before an epic match is setting his or herself up for failure. Due to the long recovery time, athletes want to save that strength for competition and not for working out. “Working out” during the season is generally at a lower frequency and intensity so as to just maintain what an athlete can do while minimizing needed recovery.

Again, as a pure beginner, strength gains are possible amidst other intense activities. But once somebody is advanced, that person has to become discriminating about when to expend maximum effort. Planning for recovery becomes necessary to the more advanced trainee. After a certain point, a decision has to be made about goals, and that further strength gains have diminishing returns. Alternatively, an individual may decide that very-advanced strength is worth it, at the cost of requiring several days a week of full-recovery. It’s a personal choice.

Conclusions: Becoming a Supple Leopard

The pain in my hip over the last month has been really annoying, although in the grand scheme of things it hasn’t been all that bad. Whenever I broke into a run to get across the street I felt a shot of pain. Whenever I bent over to pick something up I got a shot of pain. Whenever I was lying down and rolled onto my right side I got a shot of pain. It’s healing well so I’m not concerned, but I can only imagine what a more serious and permanent, injury would do to my quality of life.

I would feel foolish, guilty even, if I did something to myself in pursuit of advanced strength that lead to me requiring body-part replacements before I’m even a senior citizen. One of the many benefits of strength training is supposed to be injury prevention, and for the most part it is unless you take it to the extreme like these guys.

This summer, I read the awesomely titled Becoming a Supple Leopard (BASL), by Dr. Kelly Starrett. In a nutshell, BASL is an excellent guide on how to move in the way that our bodies were designed to move. If movement patterns are a bit off at a young age, these movements get woven into our habits as we get older. Eventually it can turn into one of those injuries where a movement is performed “normally”, and a ligament just goes *snap*, and the athlete is left thinking “but that’s how I always do it! Why did I get hurt this time? Bad luck!”. Not bad luck; bad form. In the words of Dr. Starrett: “You can move with bad form until one day you can’t”. Humbling.

For me, I had to realize that being excessively “duck-footed” (feet pointed out as opposed to straight forward) was going to cause me problems long-term. I’m now forcing myself to point my feet straight ahead and although it still feels unnatural, it is becoming more fluid every day. Along with how to move, there is a large section on how to regain mobility in your joint and tissues and how to maintain it once you have it back. In a way, this is more important than strength; it is how to use your strength properly.

I now have different goals from the ones I used to have. For a couple years my only real physical goal was to get stronger. Now that I am quite strong (for me), my physical goals are shifting towards being able to use my strength as long as possible without injury (like a supple leopard…), and be at peace with the fact that I might not get any stronger. It’s going to be an adjustment for me, and I see this with other advanced lifters. The mentality has to change so that, quite often, a workout will mean not going to 100%. All that’s going to happen in a workout is to accomplish something you already know you can do and be satisfied with that. This way, I’ll only rarely be totally exhausted and can bust into a jog or lift some heavy-ish things spontaneously without having to worry about anything (again, like a supple leopard…). Being able to deadlift 400 pounds is really good. 500 would be better, but it’s probably not worth it. This line of thinking may change. We shall see.

I hope you got some value out of this! Message to my friends: Get strong enough, and then stay that way.

I am drug-free, 45 years old and have built a 2XBWT deadlift in 3.5 years of lifting (525 lbs @ 260 lbs). Since I have recently pulled 475 with a snatch-grip, it looks like I am going to hit 550+ conventional at the end of my next cycle.

A lot of trainees don’t seem to understand the difference between building strength and demonstrating strength. When you were pushing it for 4 reps at 395, you were demonstrating strength. If I was training to hit 405 x 5 on a test day, the most weight I’d use for 5 reps would be about 350 and this for just one set (135 x 5, 225 x 5, 275 x 5, 315 x 5 and 335 or 350 x 5). The deadlift is the most unforgiving lift there is. I never test my strength in a regular training session, and I will take 10 days off from heavy pulls before testing or competing. This is why I feel very strong on the day when I push myself to the limit.

Prior to hitting 475 snatch-grip, I trained with singles in the 315-365 range (70 to 80-ish% of my prior max, which was 440). The last session 10 days before the test was the heaviest one, and it was the only time I used 405 or more (405, 3 x 1, then 425 x 1). On test day, I hit 475 after an easy 455.

Using less weight allows me to train more often and recover better. Using singles (most of the time) prevents my form to deteriorate, which is something I absolutely don’t want when I’m pulling 400+.

Last year, in a strongman competition, I deadlifted 455 lbs for 10 reps. There is just no way I could do that in training, but my body was well fed and well rested on competition day (as it should). My heaviest set prior to this meet was 455 x 4 (leaving at least 3 good reps in the tank – but I was giving all my power into every single rep). Build up your strength! Don’t try to grind through a plateau.

Last: I don’t advocate back-off sets. If I am using singles and notice that the lifts are slowing down, I stop. If I am using reps, I’ll ramp up to a top set; up to a triple at 80-85% is typical, but then that’s it; there is no other set. I want to train the deadlift when I am at full strength. A lot of injuries happen when a considerable weight is used by a tired lifter.

I’d say this: don’t chase big weights in training. Keep lifting sharp with good technique, and do this on a regular basis; you will get stronger. If I was playing sports, I’d stick to singles or doubles deadlift in the 65-70% range with a focus on power and speed (with proper technique) so I can maintain a high level of strength without compromising performance on the field.

Hey Dominick,

Thanks for the great comment! There’s a lot of good content in there, and I can tell you know what you’re doing. I really appreciate you contributing.

I wrote this article about 4 years ago, and have learned since then. I could update it at some point.

Lately, I’ve fallen into what you advise. I’ve been training at about 70% of my maxes, and I agree with what you say. I’m staying strong and sharp, while minimizing needed recovery. It feels good and I can play sports at a high enough level for me. I haven’t gained considerable strength in a while, but I haven’t really tested myself either.

For lifting while you’re playing sports – how many sets of singles/doubles in the 65-70% range would you recommend?

When I was going through what inspired this article, I was following the Leangains (Martin Berkhan) approach of the RPM (reverse pyramid training), where he advocates a low frequency of training, and shooting for a personal best every workout. This obviously works for some people (like him), and made for fast progress when I was a beginner, but after I became more advanced left me burned out and increased my injury risk, hence the story at the beginning. Perhaps it’s what you say – it was too close to demonstrating strength, without enough building of strength.

One thing I’ll say is that, while your advice is clearly great and useful, it still applies to people who’s goal is to maximize strength, which is totally awesome, but becomes somewhat highly specialized and for most people, has diminishing returns. For someone who wants to become incredibly strong in an intelligent way, I agree with you and learned from your comment. For those who want to be strong enough to be highly athletic without training becoming a major focus, I stand by my strength goal recommendations, as they can be achieved relatively quickly and have incredible benefits compared to the effort involved (for a complete beginner). I’m not saying that there’s no point in going further; there clearly is. What I mean is that the benefits compared to the effort involved start to lean in favour of backing off at a certain point. Where that point lies is up to each individual. I truly admire your focus in becoming as strong as you are. Also, not that you’re old, but you’re older than me, and this is inspiring. I’ve started to have thoughts that, at 32, my physical peak is behind me. Maybe I’ll have a second go ’round on building up strength in my 40’s! Seems to be working for you!

Thanks again for the comment! I’m going to bust out some sets of 2 or 3 at 70% on squats tomorrow!

– Graham

“For lifting while you’re playing sports – how many sets of singles/doubles in the 65-70% range would you recommend?” – For deadlifts, I’d be doing 5-10 singles or 5-8 doubles at that range, since the goal is more to maintain than build. More important than numbers is to stop when the lifts are slowing down – otherwise, fatigue will build up and the athlete risks showing up on the field with a fatigued lower body (not good!).

Keep in mind that I am not a specialised coach working with athletes (like Christian Bosse). Most of my comments apply more to the guy like me who wants to build a 600+ deadlift, which obviously requires a lot of specialised strength training.

I’ll also say that I spend some months focussing on less taxing lifts, like bringing up my press and doing more power cleans and power snatches. Dynamic lifts do a great job in keeping my body young!

Hi Dominick,

Sorry for the late reply – been a crazy summer. I really appreciate the info you’ve provided! I’ve had a great few months of training and am feeling less fatigued, but still strong. It can be hard to break the mentality that you always need to push yourself to 100%. I see a lot of younger people getting trapped up in that the way I did.

Thanks again for the comment. Very, very helpful

Graham

Hi, I came across you article and like it!

I have used your image in my article http://christianbosse.com/how-much-strength-training-do-i-need/ and linked to you as the source.

Keep up the great work

I’m glad you liked it! Thanks for the link. I like your article too.

Hi Graham;

Great article about the importance of knowing your goals when lifting. I’m assuming the squat is a back squat. Any approximate goal for a front squat?

Thanks again.

Bill

Hi Bill,

Thanks for the comment! Yes, the squat I’m referring to in this article is a back squat. For a front squat, I know for myself I have to shave off a decent amount. I’d probably shoot for 1.3xbodyweight (175 pounder hits 225 pounds).

I now recognize that different body types (different dimensions) are going to have an easier time with some lifts over others, so these are just an outline to illustrate the point I’m making. I know for me, 1xbodyweight bench took a while, but the 1.8xbodyweight deadlift was pretty easy. I think you’ll know when you’re at the point of diminishing returns by the extreme recovery time, regardless of which lift or how much weight it is.

Thanks!

Graham

Thanks again,Graham.

Awesome and needed article Graham. Been taking a similar approach with myself and clients for a while. Even with pro athletes, everybody thinks they’re killing it all the time. They’re not. They work hard, but they save killing it for practice and the games. That would be life for us mortals. There’s just other shit we wanna do. I would check into some testing, though, for your duck feet. (Although you may already have.) It could just be the bony structure of your hip sockets and femur heads, rather than muscular or motor patterning. That’s not something you want to push too much if so. I had a bad experience with a client back in the day trying to do that (though I was able to learn, adjust, and repair the damage). Dean somerset has some good self tests and talks about it a lot. If you’ve already thought of that, just ignore me.

Matthew,

Thanks for the reply! Yes, I agree that people generally think that pros are at 100% nearly all the time. I used to think that way too before I realized how much they hold back unless they’re competing (with the exception of a rare few).

About my duck feet – I have over time (wrote this article over two years ago) come to accept it as something that isn’t wrong per se, but that I was perhaps just taking too far. I haven’t looked into it too much beyond that, so I will check out Dean Somerset’s work to see if I can learn something.

Thanks for the tip! I appreciate the contribution.

Graham

“Squat: 1.5 x bodyweight (175 pounder aims for 265 lbs) Deadlift: 1.8 x bodyweight (175 pounder aims for 315 lbs) Bench press: 1 x bodyweight (175 pounder aims for 175 lbs) ”

Are we talking one rep max here or some different amount of volume for that weight?

Hey! Thanks for the question.

To avoid the point of diminishing returns, I’m talking a solid one-rep max. It may not seem like much (especially the bench..that could be a little higher maybe), but I think it’s true. Lots of people going higher, however. It’s worth it for some.

Hi Graham, nice article. I like the concept and the lifting goals.

I can lift those goals except for the 1.5 BW squat. I have put more effort into the squat and trained it more often (not too much though) because mine lags, but it is still my weakest lift. I think it is because I have long legs and a short torso, which is not good bio-mechanics for squatting. Deadlifting is so much easier and natural for me.

So my question is: assuming I have the same reasons for lifting which you outlined (health, athleticism, physique), has my squat reached diminishing returns? Or would I still benefit significantly by working towards 1.5 BW?

Hey bikebum, thanks for the comment.

I feel you on the bad biomechanics for squatting. I have a short torso and long legs and arms as well. That’s why my bench press lags my other lifts too. That being said, I did eventually surpass the 1.5 BW squatting goal. I’m actually closer to 1.7/1.8 on it these days (not pushing it much past that, mind). Why it’s lagging for you could be a number of reasons. How’s your mobility? Hips ever sore and tight, or can you chill in a squat for a few minutes with no pain? Do you fully engage your glutes, or do you rely on your quads? Do your knees hurt?

As to whether there are diminishing returns…I’d say nothing significant yet, but I’d have to know more. Are you crazy sore for days after squatting? Does the recovery time impede your performance at other activities that you enjoy? Do you feel dead inside after squatting heavy?

If you’re not too sore after, and your other activities are going well, then keep going towards the 1.5 BW goal. As I’m sure you know, squats are fundamental and totally awesome. Deadlifts too, but you seem to have no problems with those.

It doesn’t matter how long it takes you to get there if you’re enjoying it. Those goals that I outlined were where I noticed that my enjoyment faded and I stopped seeing obvious benefits to it, but it’s not the same for everyone. Only you can decide that, but I still think 1.5 BW squats are achievable by almost everyone if they want it, and there are benefits to being that strong.

Hope that helps!

Thanks for the awesome response! Interestingly my bench is one of my better lifts. Maybe because my arms are closer to normal proportions, even with the long legs.

I use to have the issues you mentioned but I think I worked them out. I can hang out in a third-world squat, although it’s kinda hard without holding a small counter-weight in front. Worked on glute activation, and I feel the squat there as well as in the quads now, and I no longer have the flat bunz! Knees feel great.

I guess my only problem is squats are really freaking hard! Last time I barely ground-out 5 reps at 185 lbs (so in theory I should be able to squat ~210, or ~1.2xBW) . Squat gains seem so much harder to achieve than with other lifts, even though my other lifts are at a higher level based on the standards.

I did recently reduce my squatting from 2 or 3 to 1 time a week, since the weather’s been great and I’ve been doing lots of biking and hiking. Once a week feels like the sweet spot for now.

Thanks for the advice. Sounds like it’s worth the effort, so I’ll keep working at it.

You’re welcome man! I would say it is worth it, based on your goals. The progress will come, and it will generally come in bursts when you least expect it (as I’m sure you’ve noticed with other lifts).

Squats ARE hard, but they pay the biggest returns (deads too). You’ll see progress if you stick with it. Squeeze those glutes hard! It took me years, but I’m now getting 5 reps at 335 pounds (I weigh 205 or so). I’m at the point now where I only go heavy every 2 weeks or so…the recovery time is long up at this weight.

Remember this too: as you become more advanced, reducing frequency is a good thing, which you’ve already done. Bigger lifts require longer recovery times. You’ll get stronger by going heavy, and then backing off more. Plus, you’ll be sore less often, as you’ve noticed.

Enjoy your strength, bro 😉