Introduction:

The last post in this series discussed how light influences your circadian rhythm, and the health effects of blue-light exposure during the day and its negative effects at night (which was discussed in Sleep Series Part 2). This post will look at the effect of the hormone cortisol and how it gives us energy and focus through the day, and then drops off and allows us to relax and sleep properly at night. Let’s take a look at cortisol!

Cortisol – the Stress Hormone:

Cortisol is a hormone produced by the outer layer of the adrenal glands (little glands right by the kidneys) that is of critical importance to the body. It is released during times of stress (physical or psychological), and has metabolic (energy-affecting) and immunologic (immune system affecting) properties helping the body properly respond to stress. For fun (hah), here’s a look at its chemical structure:

In reference to its metabolic properties, cortisol is a glucocorticoid, which means that it increases blood glucose (sugar) levels to supply energy to the muscles and brain to overcome stress. To do this, it increases the metabolic process of gluconeogenesis, which takes amino acids (building blocks of protein) and converts them to glucose. It also inhibits the uptake of glucose by the liver and muscle tissues by counter-acting insulin (which usually lowers blood glucose). Either way, when cortisol is high, blood glucose is high. Cortisol also acts to increase lipolysis (breakdown and release of fatty acids into the bloodstream).

Its immunologic properties are counter-intuitively mostly in suppressing the immune system and inflammation. Over the short-term, the immune system is viewed as non-essential to the body (why fight a disease when there’s a more pressing matter?), so cortisol diverts energy from the immune system to the rest of the body to combat the (hopefully) short-term stress. For this reason, cortisol (known as hydrocortisone when it’s used as a drug) and other glucocorticoids are used to treat medical conditions that are the result of an overreaction of the immune system (allergies and autoimmune conditions such as asthma, psoriasis, rheumatoid arthritis and multiple sclerosis). Overall, cortisol’s effect on the body is to shut down systems that aren’t needed short term, and to pour energy into the bloodstream for the stress at hand.

Cortisol often gets a bad reputation, but is entirely necessary and can even be a great help. Imagine you just ate a big relaxing meal in the early evening. In this situation, cortisol would be low and you’d be digesting and feeling a bit lazy. Now, what if a lion were to suddenly appear? You’d see it, recognize it, and your adrenal glands would quickly release cortisol (and other stress hormones) into the bloodstream. Digestion would shut down, and you’d get a burst of energy to help you through the life-threatening situation. Assuming you survived this encounter, cortisol would lower afterwards and digestion and rest would resume.

I discussed in a previous article that the stress-response is a good thing if the stress is acute (short-lived), and followed by a period of low-stress recovery. In that context, we often come back stronger and ready to handle that particular stress more effectively. As an example, this is how muscles get stronger! Intense training is a stress on the body, but if it’s relatively short and followed by sufficient recovery, we come back physically stronger and perform better in subsequent training sessions. It is only when stress and the accompanying cortisol secretion becomes chronic that we see problems. In our modern world however, the stress response is generally activated too much and we are beginning to see its negative health effects.

The Natural Cortisol Circadian Rhythm:

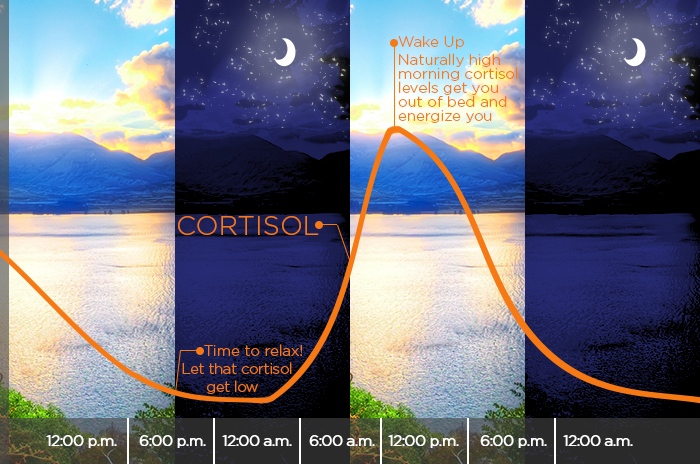

How does all this talk of cortisol relate to healthy sleep? Well, similarly to the previous post in this series on serotonin and melatonin, cortisol displays a circadian rhythm in humans as well. It looks like this:

The above diagram shows the natural cortisol circadian rhythm, without any additional cortisol being added by stressors encountered throughout the day. From the diagram, we see that cortisol is at its lowest point early in the night and slowly rises until there is a spike in the early morning to wake you up and get you moving. In an ideal situation, humans are most prepared for stressful situations in the morning and relax and unwind as the day progresses (unless of course a stressor becomes present). In our modern world, however, stress doesn’t always disappear towards the end of the day. Feeling a bit stressed and revved up in the morning is natural and can be beneficial, but when cortisol is high in the evening, it has an effect on both the quantity and quality of sleep we get at night.

Cortisol and Sleep:

It would appear from the natural cortisol circadian rhythm that low stress levels precede the sleeping period. Indeed, cortisol levels throughout the night are associated with specific sleep stages. When cortisol is low early in the night, most of the deepest and most restorative stage of sleep occurs (see Sleep Series Part 2 for explanation). Higher cortisol levels before bed-time are known to both delay the onset of sleep, and lower the quality of the sleep you get.

This study showed that stress pre-sleep (in the form of an oral intelligence test) resulted in a longer time to get to sleep and a lower subjective sleep quality. Another study showed that subjects with higher cortisol levels during sleep experienced less slow-wave sleep (deep sleep), more stage 1 sleep (the lightest stage), and earlier wakeup times for the female subjects.

Personally, I can relate to these findings. When I stop working in the late afternoon/early evening, and spend the night relaxing with a great meal and an easy conversation or some light-reading (and low-blue light exposure), I fall asleep and wakeup very easily. I stay feeling rested throughout the day (with perhaps a small dip in the afternoon), and all is good. When I spend the night working on a complicated subject requiring deep thought or I experience a social stressor, it takes much longer to fall asleep. I also wake up feeling grumpy and unmotivated, and I know the day will be harder than it would have been otherwise. I can control myself and shake off these feelings to a degree as the day progresses, but for the most part the only cure is a good night’s sleep.

The management and timing of stress is extremely important to ensure healthy sleep is obtained on a regular basis. Stressful activities early in the day are not a problem, but being stressed at night will impair sleep and the ability to cope with stressors the following day. Over time, sleep deprivation (from stress or otherwise) alters our stress-response making us more sensitive to stress. This can develop into a vicious cycle where being stressed before sleep leads to impaired sleep, which leads to higher stress levels the following day, which leads to more impaired sleep, and so on. Why, human body, why? Well, let’s learn to manage it.

Low cortisol levels in the evening are important, so the next post will explore factors that determine evening cortisol levels, and ways to bring down evening cortisol in non-ideal situations.

Until then, please my friends, relax and unwind before bed! You’ll have a much better day to look forward to. You can deal with your stressful junk in the morning.

Readers: What are your experiences with stress/cortisol and sleep? Please comment below.

– G

I can relate! I find it nearly impossible to get up from my desk and then go straight to bed to sleep. Usually results in a restless night. However, if there’s adequate wind down time before sleep, the sleep experience is entirely different. Now I understand more about why this is. Thanks, Sustainable Balance!

I can relate to that! I need at least an hour, preferably two. Thanks for the comment! Next post I will look at ways to bring down cortisol when things aren’t so ideal.