Featured photo courtesy of Gregor Winter.

Introduction:

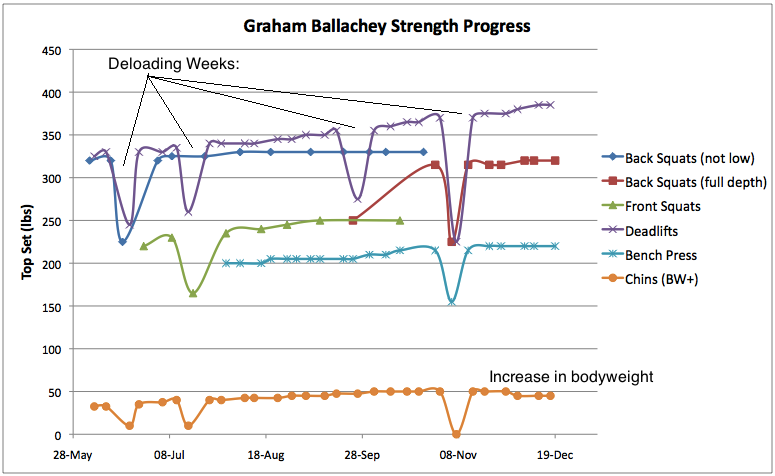

The day before I started a new job, it was a rainy winter’s day in North Vancouver, but I felt pretty good. I wanted to avoid trying to fit a gym session into my first couple days at the new job, so the day before I started I decided to go hard and make it count so I could take a few days off. This workout was going to be a “pull” day, meaning I would work on deadlifts, weighted chinups, and pendlay rows. I had worked my way up to working sets of 395 lbs on deadlifts (meaning I was aiming for 5 reps at this weight). 400 lbs was so close I could taste it. That had long been my “I know I’ve made it when” goal.

Previously I had been working a job involving some awkward lifting but I figured I was so fit and strong that I could handle the job and intense strength training concurrently. However, while working, I did something to my lower back that made it sore for a few days, but then it went away. So, on this particular day, which was several weeks later, I warmed up and could tell that my back wasn’t 100%. But hey, I love progress and my ego was tied into this, so I kept going. I hit 4 reps at 395 lbs (a personal best), but definitely did not use picture-perfect form on the last rep. My back felt all right though, so I lowered the weight to 365 lbs for another work set.

I completed the first lift and was lowering the bar back down when I felt an extremely painful *ri-i-i-p* in my lower back, near where the original twinge had been. My hands let go of the bar and I stood up. As I bent down over to take the weight off the bar, searing pain at the site of the rip got me to stand up straight again. The guy next to me had to be enlisted to get the weight off the bar and put everything away. As I walked out of the gym, I knew that I had experienced my first real weight-lifting injury. Until that point I had had zero problems in 10 years other than some sore muscles after training, which is to be expected.

For the next two weeks I could not bend my back. It had to be perfectly straight up or I got shooting pains at the site of the injury. Getting in and out of a chair required serious focus. I did a little self-diagnosis (I can’t recommend this approach, but it’s what I always do), and figured I had torn a ligament near my hip. Having done something similar to my ankle years before I knew there was only one prescription: rest and time. Lots of time. My ankle took 4 months, so I could only assume this would be about 4 months as well. Boo-urns.

A Break from Weight-Lifting – What I Noticed:

After about a month of rest (other than walking around), my back was still sore but I was a lot more functional. I was able to engage in some physical activities again, but lifting weights was still out of the question. I started with some light activity: softball, biking, and pushups/chinups. My performance was actually pretty good fitness wise (although I did drop pop-flys at softball), which indicated that I was holding onto a lot of the strength I had gained prior to the injury. I was able to run really fast, jump really high, and throw really far. Actually, I felt like I was running faster and jumping higher than I’d been able to while in the gym lifting heavy 2-3 times a week.

My appetite also decreased, which I expected to happen. When I was lifting hard 2-3 times a week, I often felt ‘hollow’ in that I would sit down and eat for an hour straight (involving more than a pound of meat), and still would want more. The days after I hit advanced weights on big lifts (squats, deadlifts, etc), my appetite would be somewhat ridiculous to the point where it was becoming very time consuming. After the month off, I was still quite muscular and strong (other than the injured back), and I was satisfied with less food, which was freeing up time.

So there I was, ironically finding lifestyle benefits from staying out of the gym. I noticed 2 main advantages: one, my non-weight lifting athletic performance increased; and two, my appetite became much more reasonable (though still really big compared to most people, but that’s just me). Over the summer my back kept improving until I was able to start thinking about weightlifting again. My first visits to the gym were just to get re-oriented, but then I started challenging myself again. The upper body lifts were no problem, but squats left my back pretty sore and deadlifts were still way too painful to consider.

About 4 months post-injury I was still avoiding deadlifts but began pushing hard with the other lifts, including squats. I got up to about 330 lbs on the squat again, a day before a softball game. As I was biking to softball I could tell that my legs were very much still in recovery from the previous day’s squat session. The hills were harder, and I was dreading them to a certain degree. Once I got to the game, I noticed I couldn’t run as fast, or throw as far. My body just didn’t have the jump it had while I was not training intensely. The appetite was also back. Big lifts make for big meals.

I quickly realized that I needed at least 2 days or more of recovery between extreme weight sessions if my body was to perform near its peak again. Scheduling my weight sessions around sports was annoying since sports’ schedules change from week to week. It came to a crossroads: I had to choose whether to continue getting stronger and accept the fact that my athletic ability would be compromised most days, or I had to accept that I wasn’t going to get any stronger allowing my athletic performance to improve. Essentially:

Choice 1 – Gain more strength, but be sore and weak when doing anything else

Or

Choice 2 – Maintain (advanced) strength, and perform better at everything else

When I was a strength novice, I didn’t have to make this choice. Back when I thought 200-pound squats and 150 pound bench presses were immense, the recovery time wasn’t as long. I could play sports the next day, no problem, as long as I had been training regularly so the soreness wasn’t too bad. It was only when I took a break due to injury from advanced training that I noticed I could play harder by avoiding 300-pound squats and 400-pound deadlifts, at least for the few days before a game.

Six months post-injury I was able to deadlift intensely again, working my way back up to 380 pounds. I was able to do it, and felt fine in the gym, but I woke up the next morning with a very sore right hip. Like, bad sore. It’s been a month since I woke-up with that sore hip, and it is only now recovered to the point where I’m thinking about weight-lifting again.

This time I’m going to listen to my body, and make the decision that I’m strong enough.

The Diminishing Returns of Strength Training:

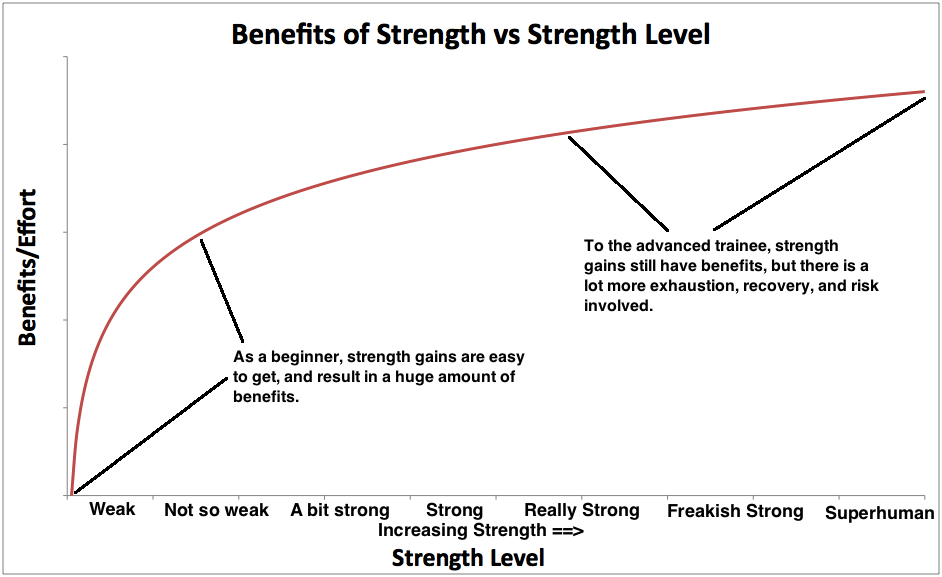

I have written a lot about the benefits of strength training, so I won’t get into it again here. If you’re curious, start here. When I started strength training, it was easy to make gains and I noticed nothing but benefits for a long time. Everything I did, I did better. I felt (relatively) superhuman when I played sports. I was running faster, jumping higher, throwing further, had more endurance, could take bigger impacts, and overall just felt more confident.

Once I became advanced, however, incremental increases in strength did not provide the same returns they did when I was a beginner. They were also a lot harder to attain. Going from a 150-pound squat to a 200-pound squat gave me a ton of new athletic ability. Going from a 300-pound squat to a 350-pound squat did not provide the same return on investment. It took a lot longer to get to a 350-pound lift from 300, the recovery time in between sessions was much longer, and I had to eat a lot. These circumstances applied to all my lifts.

On top of the increased recovery time, the risk of injuries from weight-lifting increases dramatically once you are advanced. Even without picture-perfect form I never got injured lifting weights when I was only moderately strong. There just wasn’t enough weight to do any serious harm. Once I got strong enough to handle serious loads, that’s when aches and pains became common. And if I didn’t have laser focus in the gym, it was straight-up dangerous.

Part of me wants to be as strong as possible, but I realize now that it comes at too great a price (for me). If I wanted to be a master weight lifter (which I’m not even 100% sure I could be), it would be at the expense of too many other physical goals. I like biking places, playing spontaneous games of pickup, and I wouldn’t want to limit myself from taking up other physical hobbies. To stay at my current level of strength, 1-3 moderate to high intensity workouts a week are all that’s needed, which doesn’t require much recovery if the goal is only maintenance. To sum up these thoughts, I made the graph below. “Benefits/Effort” (benefits of additional strength divided by effort) on the vertical axis suggests that although strength gains always result in benefits, the effort to get that strength gets so large once you are advanced that it’s less attractive as a goal. Click on the graph below to get a better view of it.

The diminishing returns of strength training are real. The concept of being strong enough is an important one. Until this point, I had experienced nothing but benefits to being stronger, but eventually this was no longer the case.

What is Strong Enough?

This is not a reason to avoid weight lifting entirely as there are too many benefits to ignore, but it important to determine exactly what you want out of weight-lifting. If it’s just improved health, strength, athletic ability, and physique I would recommend the following goals (which are based on nothing but experience and observation):

Squat: 1.5 x bodyweight (175 pounder aims for 265 lbs) Deadlift: 1.8 x bodyweight (175 pounder aims for 315 lbs) Bench press: 1 x bodyweight (175 pounder aims for 175 lbs) Pullups: 8 consecutive solid pullups *If you’re female, shave a bit off these, unless you really want to go for it!

That’s it. If you can do all that, you are strong enough to obtain the vast majority of the benefits from strength training. To a beginner these may seem really advanced but it isn’t all that hard to achieve in 1-2 years with disciplined training, depending on the starting point. There will be individual variability due to different body types, so some of these goals will be easier to achieve than others, but there’s no reason almost anyone can’t do what’s described above if this is a goal for them.

The lack of return on investment that I’ve been mentioning only started to happen when I went well beyond these goals. Once I started thinking along these lines I looked into what professional athletes do for training. It turns out, as obviously as can be, that off-season training is inherently different from the training that occurs during a pro-sports season.

For a pro-athlete the goal of the off-season is to increase strength and conditioning to become a better athlete. During the actual sports season the goal is to win games. During the season an athlete who tries to set a personal record on the deadlift or squat the day before an epic match is setting his or herself up for failure. Due to the long recovery time, athletes want to save that strength for competition and not for working out. “Working out” during the season is generally at a lower frequency and intensity so as to just maintain what an athlete can do while minimizing needed recovery.

Again, as a pure beginner, strength gains are possible amidst other intense activities. But once somebody is advanced, that person has to become discriminating about when to expend maximum effort. Planning for recovery becomes necessary to the more advanced trainee. After a certain point, a decision has to be made about goals, and that further strength gains have diminishing returns. Alternatively, an individual may decide that very-advanced strength is worth it, at the cost of requiring several days a week of full-recovery. It’s a personal choice.

Conclusions: Becoming a Supple Leopard

The pain in my hip over the last month has been really annoying, although in the grand scheme of things it hasn’t been all that bad. Whenever I broke into a run to get across the street I felt a shot of pain. Whenever I bent over to pick something up I got a shot of pain. Whenever I was lying down and rolled onto my right side I got a shot of pain. It’s healing well so I’m not concerned, but I can only imagine what a more serious and permanent, injury would do to my quality of life.

I would feel foolish, guilty even, if I did something to myself in pursuit of advanced strength that lead to me requiring body-part replacements before I’m even a senior citizen. One of the many benefits of strength training is supposed to be injury prevention, and for the most part it is unless you take it to the extreme like these guys.

This summer, I read the awesomely titled Becoming a Supple Leopard (BASL), by Dr. Kelly Starrett. In a nutshell, BASL is an excellent guide on how to move in the way that our bodies were designed to move. If movement patterns are a bit off at a young age, these movements get woven into our habits as we get older. Eventually it can turn into one of those injuries where a movement is performed “normally”, and a ligament just goes *snap*, and the athlete is left thinking “but that’s how I always do it! Why did I get hurt this time? Bad luck!”. Not bad luck; bad form. In the words of Dr. Starrett: “You can move with bad form until one day you can’t”. Humbling.

For me, I had to realize that being excessively “duck-footed” (feet pointed out as opposed to straight forward) was going to cause me problems long-term. I’m now forcing myself to point my feet straight ahead and although it still feels unnatural, it is becoming more fluid every day. Along with how to move, there is a large section on how to regain mobility in your joint and tissues and how to maintain it once you have it back. In a way, this is more important than strength; it is how to use your strength properly.

I now have different goals from the ones I used to have. For a couple years my only real physical goal was to get stronger. Now that I am quite strong (for me), my physical goals are shifting towards being able to use my strength as long as possible without injury (like a supple leopard…), and be at peace with the fact that I might not get any stronger. It’s going to be an adjustment for me, and I see this with other advanced lifters. The mentality has to change so that, quite often, a workout will mean not going to 100%. All that’s going to happen in a workout is to accomplish something you already know you can do and be satisfied with that. This way, I’ll only rarely be totally exhausted and can bust into a jog or lift some heavy-ish things spontaneously without having to worry about anything (again, like a supple leopard…). Being able to deadlift 400 pounds is really good. 500 would be better, but it’s probably not worth it. This line of thinking may change. We shall see.

I hope you got some value out of this! Message to my friends: Get strong enough, and then stay that way.